The Murder of Andrew Jackson

July 4, 2024

We have had a terrible thing occur here ”

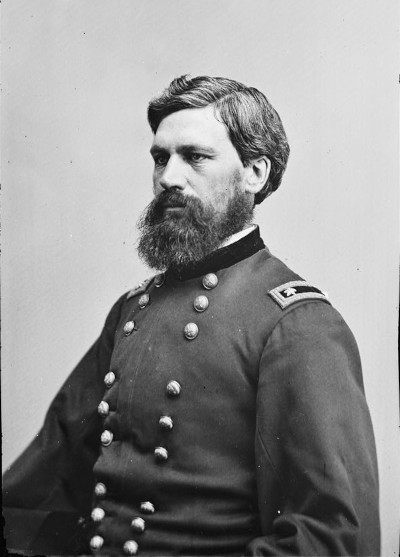

I n January of 1863, while the Army of the Potomac was encamped for the winter near Falmouth, Virginia, a murder occurred. It is one small, long-forgotten tragedy dwarfed by the larger tragedy of the American Civil War, which nevertheless deserves to be remembered. On January 14th, Brigadier General Oliver Otis Howard, commanding a division in the 2nd Corps, wrote to his wife Lizzie: "We have had a terrible thing occur here, that has cast a shade over our life at Head Quarters."

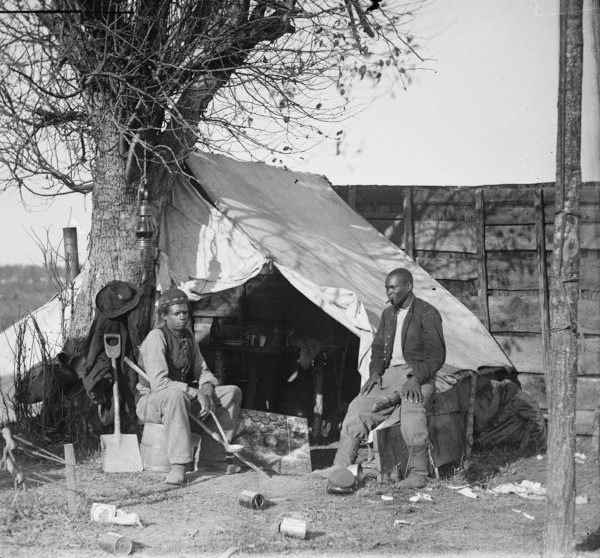

Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation had just gone into effect, and there was a general feeling of great excitement and optimism among the escaped slaves, many of them just boys, who had sought refuge with the Union army and were employed as servants. "You should see our colored boys around these Hd. Qrs.," Howard had written just ten days previous. "They are all learning to read."

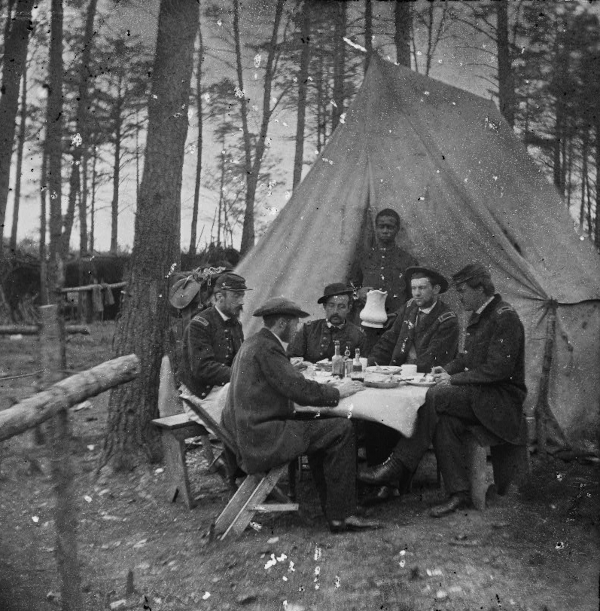

One of these refugees was Andrew, a teenage boy who worked for Lieutenant William R. Steele, an ordnance officer on Howard's staff. Also referred to as Jackson, Andrew was most likely named after the former president. He waited on the officers at table and exercised Steele's horse, among other duties. Howard described Andrew as "a mulatto of some eighteen years, of handsome figure, pleasant face and manners, and rather well dressed for the field. He appeared a little proud, especially when mounted on his employer's horse."

On Monday, January 12th, while he and another boy were returning on horseback from Falmouth with a load of clean laundry, Andrew was accosted by a couple of men identified as stragglers from the Irish Brigade. One of the men demanded that Andrew get off the horse and let him ride, but the boy refused; he was taking clothes to General Howard. The man cursed Andrew, declared that he'd "fix" him, raised his gun, and shot the boy. Despite being badly wounded, Andrew managed to ride back to headquarters, and his friend even managed to retrieve the washing that he had dropped.

Charles Howard, General Howard's younger brother and a member of his staff, described the boy's injuries in a letter to their half-brother, Dell. "The ball & buck shot had entered just below the shoulder from behind shattering the shoulder blade breaking through the joint and coming out in front - at least a portion of the charge, making a terrible ragged wound."

In an attempt to save the boy's life, doctors removed his arm at the shoulder, as well as part of his shoulder blade and collarbone. "We would gladly have had been spared these painful operations not believing that his life can possibly be saved," Charles wrote. "But the surgeons are supreme in these matters. He passed blood from the lungs from the first indicating that this vital organ was pierced."

Despite the doctors' best efforts (or perhaps in part because of them), Andrew died the day after the shooting. Before he died, Charles wrote that "He was also a praying boy and it seems to us all that it will be a great mercy if the Lord shall see fit to take him to Himself at once, sparing him further suffering and an undesirable future in this world." General Howard, having himself lost an arm at Fair Oaks the previous year, would have been all too aware of the difficulties that the boy would face, should he manage to survive. Charles, who was very close to his brother Otis, would have understood as well. For a young, uneducated man of color, it was an undesirable future indeed.

very much beloved at these Head Quarters ”

"The poor boy breathed his last breath of anguish in the night," Charles wrote on January 14, 1863, to their mother. "It is a great relief to our feelings to know that he is at peace with his Saviour whom he told Otis he loved and on whom he was wont to rely. He was remarkable for his piety and unvarying good conduct." The Howard brothers further described Andrew as "a most exemplary boy, remarkable for his good manners and strict integrity of character," "kind and thoughtful at all times," and "very much beloved at these Head Quarters by every-body."

In his diary, Charles described the boy's funeral: "We buried him yesterday P.M. Capt. Whittlesey read a passage & offered prayer - Our servants were there & a few soldiers who assisted at the burial. He was wrapped in his blanket & put by the side of the remains of soldiers who have died in service of their country. Few soldiers are laid in coffins - It seems almost barbarous to our people at home. It seems to me that thus much respect ought to be shown to the dead - to procure some enclosure of wood. But in reality it matters little. The lifeless clay that remains when the soul has departed is of little value."

The good boys blood is upon them - and God will require it at their hands. ”

Though the brothers visited General Winfield Scott Hancock in hopes of tracking down the murderer, it was of no use. "The soldier who shot him has not yet been caught," wrote Charles Howard, "- all that is known is that he belongs to the Irish Brigade famous for fighting abroad but here famous for rowdyism & villainy more than anything else." Though it is unclear how it was known that the perpetrator was from the Irish Brigade, prejudice against the Irish was widespread in the United States in those days, and a tale of Irish mischief would be readily believed.

General Howard held out hope that the perpetrator might still face divine punishment for his crime. He wrote to Lizzie: "He has gone to his God, but the murderer has not yet been found. In the Irish brigade they are so clannish that they will screen each other from all deserved punishment. The good boys blood is upon them - and God will require it at their hands."

This tragic occurrence made a deep impression on the man who would later become the head of the Freedmen's Bureau and one of the founders of Howard University. Decades later, he would write about it in his autobiography. "Among our enlisted men there were not a few who at one time held views similar to the New York rioters of 1863. They hated a negro except as a slave, and they kept alive in their circle of influence an undercurrent of malice more or less active."

Though some of the details of the event had changed in his memory in the intervening years, the essence of the story was the same. "Evidently on account of his color he was slain," Howard wrote. "Friendly voices murmured against the crime, and with set teeth echoed the settled thought: 'Slavery must go.'"

References

- Oliver Otis Howard Papers, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine

- Charles Henry Howard Collection, George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine

- O.O. Howard, letter to Elizabeth A. Howard, January 4, 1863, OOHP

- C.H. Howard, letter to Rodelphus Gilmore, January 13, 1863, CHHC

- O.O. Howard, letter to Elizabeth A. Howard, January 14, 1863, OOHP

- C.H. Howard, letter to Eliza Gilmore, January 14, 1863, CHHC

- Charles Howard diary, January 15, 1863, CHHC

- Howard, O. O. (Oliver Otis), 1830-1909. “Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major general, United States army.” New York, The Baker & Taylor Company, 1907.

- Antietam on the Web: William Randolph Steele

- Wikipedia: William Randolph Steele

- Image: Culpeper, Va. "Contrabands" , Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

- Image: Brandy Station, Va. Dinner party outside tent, Army of the Potomac headquarters , Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

- Image: O.O. Howard , Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division